Waankam: People for the Estuary is a citizen initiative located in Duluth, MN working to protect the environment, specifically the St. Louis River and Estuary, by imbuing the ecosystem with the same legal rights that are recognized for people. The 12,000-acre St. Louis River Estuary is the largest freshwater estuary in North America, the headwaters of the Great Lakes, and the largest U.S. tributary of Lake Superior. The initiative is part of a wider, global effort to recognize the “rights of nature,” which has taken root in many nations and communities around the world. In 2008, Ecuador became the first country in the world to incorporate the rights of nature into its constitution. People for the Estuary hope to introduce a City Charter for Duluth, MN that declares their mission to secure rights for the St. Louis River Estuary out of the hope that humans can become more consciously aware of our role in supporting regenerative life and take the steps necessary to do so.

Estuaries are among the most productive ecosystems on earth and hold a special relationship with the indigenous peoples who made them home, seasonally or permanently.

The rights-of-nature philosophy, consistent with an Indigenous worldview and modern systems-based ecology, sees nature as entity rather than resource. Our historic use of nature as property has led us to the climate crisis on a broad scale and degradation of the St. Louis estuary on a smaller one. People for the Estuary is working to achieve personhood status for the waterway. This status would allow the group to act as legal guardian for the estuary and to represent it in court, to win compensation for damage from development, industry, and other sources but also to proactively prevent the need for restoration and remediation. The group is led by a core group of 4: Barbara Akre, Ricky DeFoe, Emily Levang, and Zhaawanangikwe—Leah Prussia. It includes Indigenous and white members who work to restore the estuary to Waankam, or “water’s most pristine state,” in which it has been a source of clean fresh water, a biodiverse haven for 238 bird species, and a nursery for 45 species of fish.

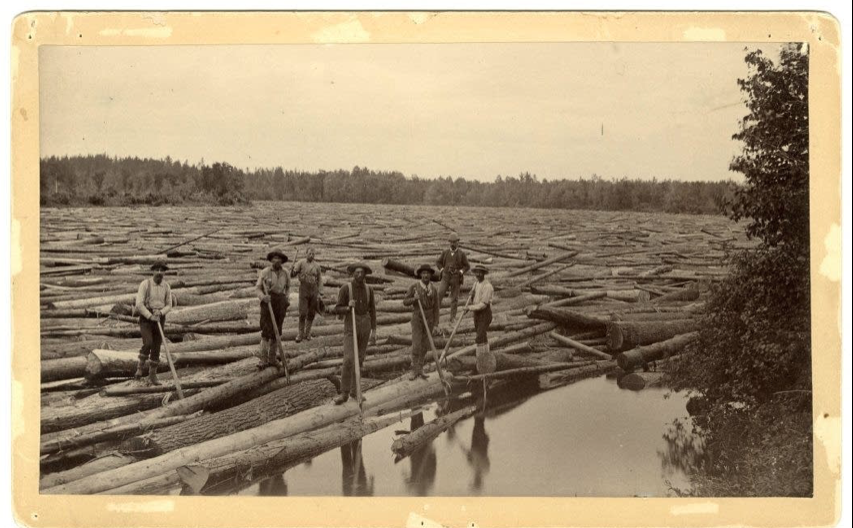

Lumberjacks on a log driver down the St. Louis River near Duluth in 1888. Photo: MPRNews.org