Cheryl Cail, Vice Chief of the Waccamaw Indian People in Horry County, South Carolina has many things on her mind these days: the “pencil and paper erasure” of her people; the now contaminated land of her ancestors that was once referred to as a “Hollowing Wilderness”; the tainted drinking water; and the repetitive flooding in Myrtle Beach, Conway, Bucksport and nearby communities.

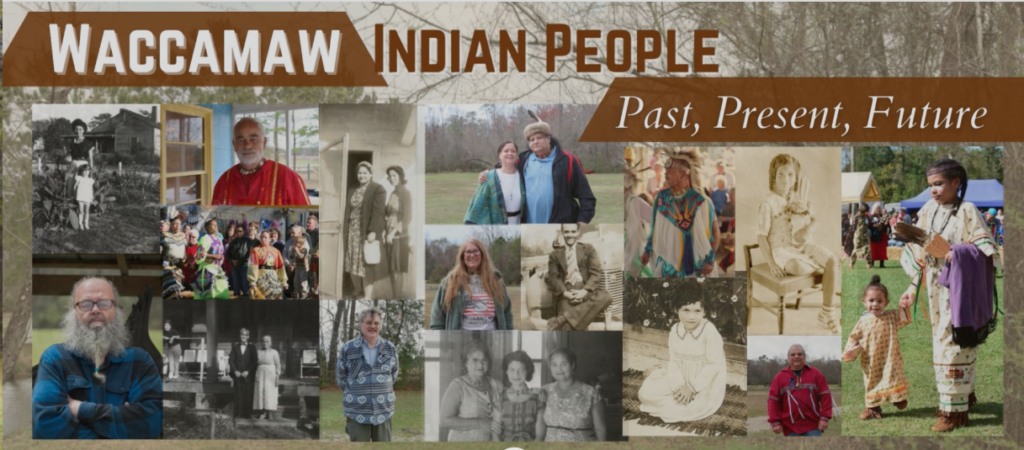

She helps lead the tribe headquartered in Aynor, SC. Founded in 1992 by Chief Harold D. “Buster” Hatcher, the group is dedicated to educating everyone on the Waccamaw’s past, present, and future. Ancestors of the Waccamaw lived in the Carolina north coast as far back as 10,000 years ago, according to archeologists, and historical records which show their interactions with European explorers dating back to the 1600’s. By the 1700’s, disease and enslavement drastically decimated their population — only to be further diminished in the Waccamaw War. In fact, one account claims that as of 1720, the Waccamaw were “wiped out.” Cail and the Waccamaw Indian People are determined to set the record straight.

“Because we’ve been ignored, essentially erased, racial reclamation is our mission. It’s likely been too long to reclaim our land, but we want to reclaim our culture, the remains of our ancestors, and continue to protect the land,” Cail said.

The land surrounding the former Dimery Settlement is sacred. Cail’s great, great, great grandfather bought 300 acres in the Dog Bluff area of Horry County in 1813 and many members of the tribe today trace their ancestry there. In 2004, 20 acres of the original settlement were purchased and donated to the tribe, arguably the Waccamaw’s own land, where they now have their tribal office and hold their annual Pau Wau. The following year, the tribe was officially the first recognized tribe by the State of South Carolina. They envision their tribal grounds — replete with a park, trails, and gardens — becoming a living museum.

Coastal Carolina University in nearby Conway sits on part of the traditional Waccamaw Indian People territory. Collaborating with the tribe, students created a traveling museum exhibit, currently at the Horry County Museum, with a digital home for Waccamaw Indian People: Past, Present, Future, chronicling the rich history and culture of the tribe.

The history of the Waccamaw is not the only thing the tribe seeks to bring to light. In 2018, after Cail’s 20-year-old son was diagnosed with cancer, she learned of PFAS (per- and polyfluoroalkyl) contamination in the groundwater at the former Myrtle Beach AFB, near where they live. After years of using foam to extinguish fires in their training activities, the Department of Defense closed the facility in 1993, and began transferring the land, but never disclosed the contamination or the lack of safe disposal methods. Today, toxic chemicals from firefighting foams may be found at 11 military bases in the state, according to a DoD report in 2019, and the South Carolina Department of Health and Environmental Control has been establishing strategies to address the impacts of PFAS in water.

As part of the National PFAS Contamination Coalition, Cail works to raise awareness of the impact of PFAS contamination to both the environment and people. But there is a lot of work still to be done to identify the areas that are experiencing the greatest harm. Phil Brown, Professor of Sociology and Health Science at Northeastern University, who heads up The PFAS Project Lab and collaborates with the National PFAS Contamination Coalition, recently posted, Toxic chemicals found in virtually every SC river tested. Action needed, critics say.

“There are a lot of areas that should be designated as SuperFund sites because of PFAS contamination,” Cail said. “There is not enough oversight, and permits to pollute are given out without real accountability — in essence, industry has been given permission to pollute. We need to connect that harmful impacts to people are a result of harm to the earth itself, our rivers, and all of our relations.”

The indigenous view of how to interact with the earth is one lesson the Waccamaw strive to share.

“The world most of society lives in today is extractive, without gratitude for the earth. Everything seems so essential to have, but it’s not really,” Cail says. “The solution is simple: we have to find ways of living that reconnect us.”

And finding ways to help other communities, in harmony with nature, guides Cail. In Bucksport, a community within the Gullah Geechee Corridor, where flooding is a persistent problem, and heirs property creates issues of land loss, it is a pressing need. In collaboration with American Rivers, the Bucksport Community Partnership, of which Cail is a part, is bringing to light the environmental justice issues in Bucksport — a place often flooded by the Pee Dee and the Waccamaw Rivers, and too often ignored.

In June of 2022, the Partnership kicked off the first of a series of community garden events. They built rain gardens with native, culturally significant species to minimize flooding, filter pollutants, and beautify the landscape. They worked with residents to choose the sites most flood-prone and encouraged more nature-based resilience methods. This is just the beginning of the vision for the Bucksport community. Additional gardens are scheduled to be installed in the Spring of this year, and the Bucksport history, modeled by the Waccamaw Indian People exhibit, is being developed. “There are many rich histories across this state and more of them should be told,” Cail said.

“Working with Kevin Mishoe, the President of the Association for the Betterment of Bucksport, I see how important it is to continue finding ways to help. It’s gratifying to do this work, but it’s also challenging to keep community members optimistic when they’ve been overlooked for so long,” Cail said. “But I’m not going anywhere. I will work until there is equity across the board.”

For more information:

Waccamaw Indian Chief Hatcher receives honorary degree from CCU, My Horry News, May 2023

What BOW is doing to address PFAS in waters of the State

‘We’re still here:’ Hundreds gather for Waccamaw tribe pauwau, ABC 15 News, Nov. 2022

Native America Calling: Tribal Leadership discuss citizenship and identity, Indianz.com, Nov. 2022

Waccamaw Indian Tribe Chief reflects on Indigenous Peoples’ Day, ABC 15 News, Oct. 2022

CCU exhibit on Waccamaw Indian People garnering national recognition, ABC 15 News, June 2022

Waccamaw Indians believe they will finally be acknowledged, My Horry News, Aug. 2021

Contact

Vice Chief Cheryl M. Cail

Website

Social Media

Climate Impacts

Flooding, Hurricanes/Tropical Storms, Water Contamination

Strategies

Affordable Housing, Art Activism, Community Farm/Gardens, Community Land Trusts/Land Conservation, Fighting Industrial Contamination, Green Infrastructure, Halting Bad Development, Policy Reform

501c3 Tax Deductible

Yes

Accepting Donations

Pending