Charleston, South Carolina is a beautiful city, swaddled in history, picturesque views and remarkable architecture, drawing tourists from the world over. But some stories in the city are hard to celebrate, particularly those of flood management policies and the history of permitting for new development.

The area known as “Downtown” or the Charleston peninsula, is surrounded on three sides by the Ashley River, the Cooper River, and the harbor, which is roughly six square miles of water connecting the inland to the sea. Business Insider included Charleston in a list of 8 American cities that could disappear by 2100. Given the onslaught of climate change and sea level rise, this is hardly a surprise to the residents of Charleston. But the city officials seem to operate under a different reality.

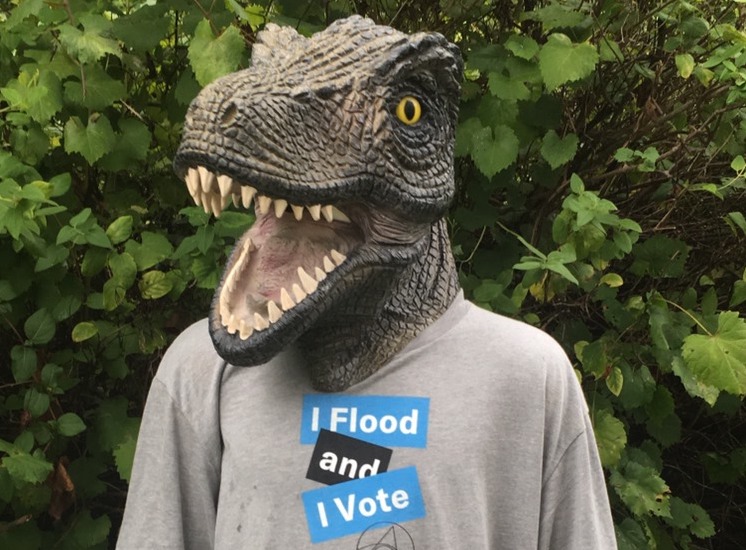

In 2005, Ana Zimmerman and her family became first-time home buyers in Charleston. In preparing for the purchase they had researched school districts, hoped for a backyard and did their due diligence in asking about the impact of Hurricane Hugo (1989) and the legacy of flooding in the area. At every turn, they were told, “no, there were no problems with flooding on this property.” They settled in and made it home.

Ten years later, the house flooded. From October 1-5, 2015, a “Thousand Year Flood” hit Charleston. With a combination of stalled weather fronts and tropical moisture streaming in from Hurricane Joaquin to the east, some areas experienced more than 20 inches of rainfall in those 5 days. Many locations recorded rainfall rates of 2 inches per hour.

The result was thousands of dollars of damage for the Zimmerman family. Although it was a nightmare, with the idea that this was a singular event, they decided to take the $80,000 NFIP payment, make up the difference and rebuild. This was after all a home they loved.

Two years later, Ana felt their lives were returning to normal. Then it happened again. This time it was Hurricane Irma. When it made landfall in Florida, Hurricane Irma was a category 3 and as it moved north it created the worst tidal surge in Charleston since Hurricane Hugo, nearly 10-feet high. Ana’s home was surrounded by water coming from 4 directions. This time the FEMA Adjustor declared her family’s home a total loss. Ana received a Substantial Damage letter from the City of Charleston with a strange acknowledgement; this was the first time the city had issued such a letter in its history.

Ana found this astonishing and with a scientific background, felt she had to investigate. What she found was that in addition to the lack of Substantial Damage Letters, Charleston had NFIP and FEMA violations, had not been doing inspections after floods, nor were they permitting flood repairs. Ana started to talk to previous residents in her neighborhood and at the same time found her FEMA claim had been denied due to building code violations. In the end, she discovered that her entire subdivision had been built below the FEMA required elevation of 12 feet; up to three feet below. Variances had been approved that violated the regulations. Her home had been destined to flood. Her research prompted a fraud investigation by FEMA. Unfortunately, the violations continue. But so does Ana.

Ana and Phil Dustan lead the Lowcountry Flooded States of America in Charleston to protect their region from flooding and destructive building practices. They are advocating for banning fill-and-build developments, revisiting old building permits, getting people out of harm’s way and building storm shelters. Ana and her family have moved to higher ground.

Written by Michele Gielis

Links

Ana Zimmerman PhD Flood History Disclosure A Case Study from Charleston, SC, June 17. 2020

Fortress Charleston: Can a Wall Hold Back the Waters?, Governing.com, June 1, 2020

Contact

Ana Zimmerman

Phil Dustan

Franny Henty

Rich Thomas

Social Media

Climate Impacts

Flooding

Strategies

Halting Bad Development

501c3 Tax Deductible

No

Accepting Donations

No